(A Green Circle Capital White Paper on Food and Beverage Mergers)

by Stu Strumwasser, Managing Director, with Francesco Lorenzetti, Associate, Green Circle Capital

November 2023 ©

If you run, own, or invested in a Consumer brand startup that now generates over $10M/year in revenue, you have graduated to the rarified air of only a few percent of those who attempt such an undertaking. Congratulations! However, if that business still generates revenue of less than around $30M/year, you may be stuck in the neutral-zone of Consumer business scale—big enough to matter, but still unable (in an industry with modest gross margin potential, especially if you use third party co-manufacturers) to be meaningfully profitable. This is particularly true for verticals like food and beverages, where margins for small businesses are usually challenging. One way or another, SMID-sized (small-to-midsized) Consumer businesses have to get to scale. Being part of a startup that is still generating operating losses is a tough place to be during a tight venture financing market such as the current one, but you may have one more option that’s open to you than you realized. If you are finding it difficult or even impossible at the moment to raise equity growth capital and get there organically, you still have options. YOU CAN MERGE. I know this may not be what you want to hear. I know that such deals are also hard to execute. You should consider it anyway. Let’s break it down.

This ain’t 2018 (and that may have been an anomaly)

I started selling investments at large Wall Street firms in 1990. I left at the end of 2005 to launch a natural soda company that I ran for six years before founding Green Circle Capital Partners around ten years ago. When I was raising capital for my own natural, non-alcoholic beverage company (between 2006 and 2010), few professional venture capital investors would look at early-stage Consumer deals, and even fewer would consider food & beverages. In the years that followed, there were some watershed deals such as Vitaminwater, Bai and Core, as well as Applegate, Annie’s, and Krave. More and more attention from VCs was placed on food and beverages. In the years between 2014 and 2018 a large number of institutional investors who had previously avoided Consumer verticals began to participate. It was a seller’s market. Access to capital increased substantially, and commensurately, so did valuations, as liquidity drives price. A new era of venture-stage Consumer investing had arrived, and it seemed like it might last.

Expectations for Founders, CEOs and shareholders of early-stage food and beverage companies became inflated in a way that probably didn’t make financial or mathematical sense. Getting a revenue multiple of 3X, 6X or even 10X at the time of a sale to a strategic acquirer could potentially be justified, but such multiples for early-stage or growth-stage startups—in an industry with thin gross margins—made for a poor balance of risk versus reward for venture investors. Yet, a mindset developed in the natural products industry that all startup food and beverage brands were being built to eventually sell to an acquirer in a life-changing exit for the founders (and a lucrative one for all shareholders). This was, in our view, an unrealistic perspective that only served to anchor stakeholders to highly unlikely outcomes. At the Fancy Food Show they have around 2,000 exhibitors. At Expo West it might be closer to 3,000. Most of them have attractive booths and innovative, better-for-you products. But how many if them enjoyed huge, marquis, revenue-multiple exits to strategic acquirers, even in the heydays? Maybe one percent? A tenth of a percent?

Shortly after the start of the pandemic, in our June 2020 white paper, “After The (Natural) Gold Rush,” Green Circle pointed out that after several years of expansion valuations and access to capital for early stage consumer brands were already declining. Anecdotally, many of the founders, CEOs, and even the investors to whom we spoke in those days did not believe us—they had “anchored” their thinking to heyday metrics—but the statistics said otherwise. In our white paper of June 2020, Green Circle stated:

Over the last five years or so there had been an acceleration in investment (and thus, in valuation) in natural and specialty food and beverage companies. It was exuberant, and perhaps irrationally so—until last year. In 2019 it began “retracing,” somewhat substantially, but quietly. On May 5, 2020 Carol Ryan published an article in the Wall Street Journal titled, “Disruptive Food Brands Get a Taste of Their Own Medicine,” wherein she explained, “Funding for these kinds of businesses is drying up. World-wide, the number of venture capital investments in consumer brands fell 26% in the first quarter of 2020 compared with the same period of last year, PitchBook data shows. Even before the crisis, investors had moved on to other hot sectors such as health care and software. Last year, venture capitalists handed over 54% less cash to consumer brands than in 2018, according to data tracked by Goldman Sachs.” That is essentially a reversal from what we had seen in the prior three to five years, but notably more in line with historical norms for early-stage venture investing.

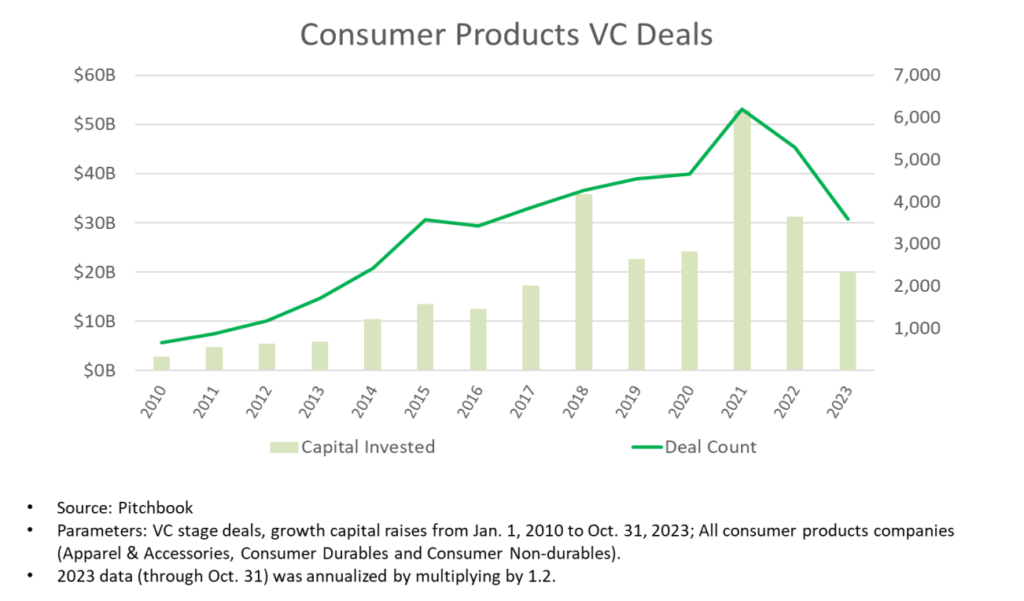

In 2020 deal activity was not substantially different from 2019, and it was down significantly from the 2018 highs. The Wall Street Journal cited PitchBook as its source for a 26% decline in Consumer venture financings in the first quarter of 2020 versus 2019. That makes sense, as the pandemic shut down everything in March of that year. However, analysis of Consumer deal activity on PitchBook for the entire calendar year shows a slight increase over 2019, meaning the second half of 2020 was strong. [Note: While it is difficult to get statistically significant data on valuation for early-stage private deals, it is easier to track the capital invested in such deals and thus extrapolate conclusions about the impact on prices]. That was then followed by 2021 and what was, in many segments of venture deal activity, the greatest year on record. The capital invested in venture-stage Consumer deals during 2021 was nearly double the level of the prior year. Understanding the many variables that led to that explosion of such financings, and the complex relationships between those factors, is not the focus of this piece—the point is that it did not last. In 2022 the market for such transactions dropped off precipitously. While the number of deals dipped slightly, around 14.6%, the capital invested in them dropped by 40.9%. More concerning is that the trend not only continued into 2023—it accelerated. Taking deal activity data for the first ten months of 2023 and annualizing it (by multiplying by 1.2) enables us to reasonably project that the number of deals this year will decline roughly another 32%, as opposed to the number of deals in 2022 (a total of about 42% below the 2021 peak and even 15.9% below the 2018 level). The amount of capital invested in those venture-stage Consumer deals in 2023 (on an annualized basis) is projected to fall short of 2022 by 35.6% (a total of roughly 62% below the 2021 peak and 44% below the 2018 level). As an aside, and for what it’s worth, while the chart below is not for a stock, and I never gave a great deal of credence to technical analysis, this chart does look like one where the item being measured has broken support levels and is heading lower.

Green Circle is a specialized boutique investment banking advisory firm that focuses on growth-stage, natural products and health & wellness companies—and we know this niche market well. This year, for example, we marketed a capital raise for a great growth-stage food brand with dramatic topline growth, healthy and improving margins, and a path to profitability in about one year. We knew it’s no longer 2018 and that it might be challenging, but we were still surprised to learn that dozens of leading venture-stage investors, who had eagerly funded such brands in recent years, now had a new barometer with which to catalyze consideration at their respective firms: profitability.

After all, at some point a business is supposed to turn a profit. Valuation is usually based upon some multiple to a company’s cashflow or a discount to some projected future cashflow. Software companies, for example, often have gross margins that exceed 80% or 85%. Such a business, which generates ten million dollars in SaaS recurring revenue, can produce six or seven million in positive EBITDA and be worth, justifiably, perhaps $100M. Conversely, a healthy food startup with some scale might have a gross margin in the 40s, and a non-alcoholic beverage brand might be in the 30s (or in the teens or 20s if either one is new and/or struggling). Therefore, a ten-million-dollar revenue food or beverage startup is usually cashflow negative. During the heyday, many such brands were able to raise multiple rounds of equity financing without ever turning profitable, but what happens if and when the VC investors decide to stop funding operating losses? You end up with a lot of CEOs looking for a chair in a room where the music has stopped.

So what’s a food/beverage startup CEO to do when the market suddenly insists on seeing profits?

Um…. make a profit? You can do it. Well, some of you can, and you may need to be creative. You may need to manage expenses better and/or you may need to get to scale through a merger. What can you not do? The same thing and expect a different result. In our experience, if the business generates under $10M in annual revenue, the options may be limited. If the business generates over $30M (it varies greatly from category to category and company to company, but that does seem to be a reasonable general benchmark), a good management team might just need to focus on the expense side of the ledger and reduce costs in order to flip the switch to breakeven. However, in between roughly $10M and $30M (in that “food and beverage neutral zone of scale”), there are many great brands and nice companies struggling because they just happen to be in a tough business at a time when it’s hard to raise growth capital.

Hypothetically, and for illustrative purposes, if two twenty-million-dollar food brands cannot turn a profit on their own but then they merge, the redundancies that could be eliminated might instantly push the now combined business (post-integration) into profitability. If not, there would also be multiple levers with which to improve margins such as extracting volume discounts from suppliers, better terms from distributors and retailer customers, opportunities for savings in logistics and warehousing and with co-manufacturing partners, and perhaps even gaining new leverage with buyers for additional shelf space and promotional opportunities. If one of the two companies self-manufactures their products and can also make some or all of the other company’s products the savings could quickly become dramatic. One way or another, the newly combined business should become profitable. “But so what?” you (and perhaps some of your investors) might ask, “it still doesn’t get us to an exit, so what’s the point?” There are many.

First and foremost, you would now own part of a profitable business. Gone would be all of the time, energy, and psychic pain invested in the Monday meetings about fundraising and the urgent need for another band-aid of short-term capital. Gone would be any existential threat to your business that took years of hard work and sweat, and millions of dollars to get off the ground. But wait, there’s more. No, doing such a merger will not get you to the finish line (which is what stops lots of operators and investors from pursuing such SMID-sized deals)—but it will get you to the STARTING line, and that is a better place to be than the neutral zone. For instance, while my firm specializes in selling companies with revenues of between $10M and $100M, and raising equity growth capital of $5M to $25M, in today’s market a $20M revenue business that loses money is very hard to finance. That said, a $40M business that generates positive EBITDA is less so. Such a business might even be able to secure debt financing more easily and/or at better terms. You are not giving up by conducting a SMID-sized merger. To the contrary, the stakeholders who make such deals in the months and years to come (while some brands in the neutral zone disappear) are the warriors who refuse to give up. They will do whatever it takes to create value and win. And some will win.

The threshold for scale at which a natural products company might get sold to a strategic acquirer goes up and down in cycles, like many things in financial markets. There was a time, not that long ago, that brands like Chameleon Cold Brew or Krave Jerky could be sold at large revenue multiples to leading global food companies when their revenues were only around $25M or $30M. Selling a business that owns just one hero brand is usually easier and will often fetch a higher valuation multiple than a business that owns a few. But today, for most large strategics, that minimum revenue number (to “move the needle” and get their attention) is typically $100M or even much more. Therefore, if you are a stakeholder in a brand that is generating $15M, $20M, or $25M in revenue, after about three or four years, you should probably just keep doing what you are doing. On the other hand, if it has been six years, or nine years, or longer, you don’t need to allow all of the value creation to be threatened by insolvency when you have other options. If you run a $50M or $60M brand that is stable but not growing rapidly, and it’s limited in terms of a line of sight to an exit, this could be an opportunity for your brand as well.

So why don’t more SMID-sized mergers get done?

There are many reasons. One of the sayings about M&A that I occasionally reinforce to my team is, “Numbers don’t do deals, people do.” People can be complicated and confusing. They aren’t always rational. They sometimes get “anchored” to 2018 or 2021 thinking. Ego is often an issue for founders or investors whose reputations (and businesses) depend on investment outcomes, and in situations where they expected, and may have told others to expect, a different result. One’s ego can also present obstacles when it comes time to decide which CEO will be the CEO of the combined entity, which CFO or Controller is retained and which one is released, etc. I would rather be the second in command on a big yacht than the captain of a ship at the bottom of the ocean, but I also respect other viewpoints.

My advice is simple: Don’t let “perfect” be the enemy of “good.” In many situations we all sometimes struggle to accept that our choice may not be between “what we have right now and what we want,” but rather, between, “what we have right now and what is realistically possible.” I once heard a great line from Mark Cuban on Shark Tank: “I’d rather have a small piece of a watermelon than a whole grape.”

I’ve had several discussions about this over the last two years which sometimes conclude when an owner or investor decides that, “The juice isn’t worth the squeeze.” On multiple occasions, I have had an institutional investor explain to me that their firm decided not to pursue this strategy for one of their portfolio companies because after the two brands are merged, they still won’t be able to secure a liquidity event in an exit. That’s true. However, what if those folks recalibrated their thinking such that they see this SMID-sized merger as the first step, not the last step? After all, if they do nothing, is the $20M and unprofitable brand somehow closer to a liquidity event on its own?

Conclusion: SMID-merge!

If you and your fellow stakeholders participate in a SMID-sized merger that eventually grows to over $100M in revenue, it may not lead to the exit that you dreamed of—but it could create a lot of value. Your Company might suddenly have greater access to new capital; it could grow organically as well as through additional M&A. Sovos Brands just did pretty well. Stonewall Kitchen seems to be cranking, one step at a time. Those business plans certainly don’t seem flawed (at least, probably not to their shareholders). According to PitchBook, Boulder Brands acquired several food and beverage brands from years 2011 to 2014, ranging from $2M to $125M in enterprise value, and then enjoyed an exit in a 2016 sale to Pinnacle Foods for over $700M. In 2025 and 2016, Amplify Snack Brands acquired several middle-sized snack food companies that allowed them to fetch a nearly $1B valuation in an exit to Hershey’s in 2018 (according to PitchBook). I’m assuming that all of the brands they folded in probably had better parties at the time of their exits than we had to commemorate the shutdown of my natural soda company in 2011!

It is true that in the first step of a SMID-sized merger, adding one plus one may not equal three or five, but it is likely to equal more than two. That said, with scale and profitability comes valuation multiple expansion. For illustrative purposes, if two $20M-revenue-cashflow-negative food companies might be worth a given revenue multiple today, it could be argued that combining them into a profitable $40M topline company could perhaps justify a 50% greater multiple. That doesn’t create liquidity—yet—but it does make everyone involved 50% wealthier on paper, and it gets them one major step closer to such a day. The question is this: When do owners/management/Boards/stakeholders finally decide to pursue a different strategy? Answer: Often, when it is too late. Sourcing, diligence, and conducting a transaction like this could take six to twelve months. Don’t wait until a loan has been called or a key supplier can’t be paid before exploring your other options.

Lastly, while not all industries are led by companies that own portfolios of multiple brands, the one you are in is! If you could own a piece of a watermelon with three or four brands that gets to nine figures in revenue, you could potentially enjoy an exit to a strategic or a PE firm, or perhaps even be part of an IPO. Such a business could potentially be recapped, providing liquidity for those who want to cash out, and allow others to continue on and forge ahead. You could even take annual dividend distributions. I know that may sound like a bizarre idea from a distant land these days, but it’s not so terrible to get a nice check every year. But first, you need scale. Not every business gets built with multiple venture financings and then has a revenue-multiple exit without ever getting to profitability. Your brand could participate in creating a great business and a lot of value if you take the first step by merging with another SMID-sized company. You may also want to consider that the dynamic (and related risk) may be this: whoever merges first, wins. Those two brands might become seen by the market as the beginning of a small platform in their respective category, whereas others might be seen as targets, and the negotiating leverage might shift to the platform with multiple targets to choose from. Green Circle is building lists of potential merger partners in different categories and we would be pleased to help.

For further information, please contact the authors: